The Chelyabinsk asteroid

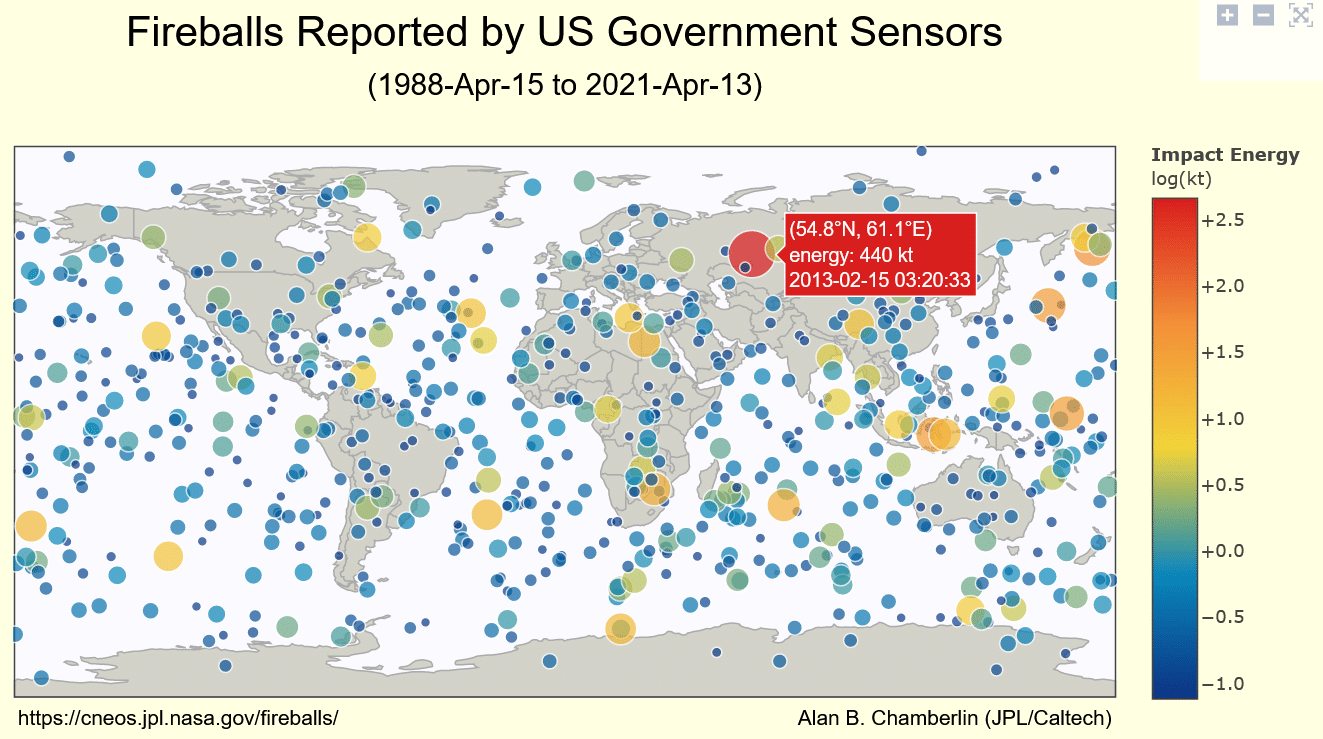

It was a cold winter morning, February 15th 2013, the people in and around the Russian city of Chelyabinsk were going about their day’s work as usual, when at about 09:20 local time suddenly a small 20-meter asteroid appeared in the sky, exploding in midair after entering Earth’s atmosphere. With an estimated force of over 400 kilotons the blast caused by the shock wave broke windows as far as 93 kilometers away, injuring more than 1.200 people and inflicting millions of dollars in damage. There was no warning, even the asteroid watchers around the world were taken completely by surprise as the asteroid was coming from the direction of the sun which made it impossible to spot him. Previously it was thought that such small asteroids pose little risk.[1] The 2013 Chelyabinsk event sparked a renewed interest in asteroids and their potential threat, which led to the creation of the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office in the USA. Its task is to lead the efforts of national agency’s as well as to coordinate with international institutions in response to the potential threat caused by asteroids.[2]

What exactly is an Asteroid?

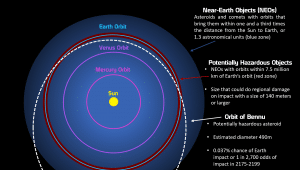

Asteroids, are rocky left overs from the early formation of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Meteoroids are fragments that have broken off larger bodies such as asteroids or comets. When a meteorite enters the Earth’s atmosphere, they can be seen as streaks of light in the sky as they are getting vaporized. If a meteorite lands on the surface it is referred to as a meteoroid. Bolides, are extremely bright meteors, sometimes also referred to as fireballs. These are caused by very large meteoroids or very small asteroids upon entering the atmosphere. In some cases, Bolides can explode in the atmosphere such as the one over Chelyabinsk. In contrast to asteroids, comets are composed of ice and dust left over from formation of our solar system. They origin lies further out in the solar system than the asteroids. When they get close to the sun, they develop visible tails as dust and gas are blown off the comet by the solar wind.[3] When the orbit of an asteroid or a comet brings it within a zone between 146 and 195 million kilometers from the sun, it can pass Earth within 50 million kilometers in which case it is classified as a Near-Earth object (NEO).[4] As of November 30, 2019, 8.839 NEOs have been discovered, with a predicted population of over 25.000.[5]

When fire and sulfur fall from heaven

The vast majority of NEOs are small objects that disintegrate in the Earth’s atmosphere before reaching the surface accumulating to 100 tons of dust particles daily. NEOs that are larger than 30 to 50 meters in size however could cause widespread damage at and around their impact sites.[6] Asteroid strikes on Earth are rare but happen on a sporadic frequency. Smaller impacts happen more frequently while larger ones are less likely, as it is shown in our planets geological record.[7] The potential damage resulting from an asteroid impact depends on whether the object reaches the ground or is disrupted and vaporized in the atmosphere, in example an air burst. In the case of small to medium sized impactors which range from about 50 to 150 meters in diameter that produce air bursts, the main hazard is the blast effect caused by the explosion, resulting in a strong over-pressure over an area of up to 100.000 km2. In addition, the thermal radiation may cause fires over large areas of 10 to 1.000 km2. Air-bursts are the most frequent hazardous impact type and are estimated to occur by an order of magnitude more frequently than those that actually reach the surface. Since Air-bursts do not form craters, it is very difficult to identify them in the geological record.

If, however an asteroid does impact in a densely populated area, it would cause millions of casualties and severe damage over distances of up to hundreds of kilometers.[8] The following table categorizes impact objects by size, and estimates impact interval, released energy and potential damage:

How likely is an asteroid impact on Earth in the near future?

Since the start of NASA’s NEO observation program in 1998, more than 90 percent of the Near-Earth Asteroids larger than one kilometer and a good fraction of the ones larger than 140 meters have been identified. It is thought that there are about 1.000 NEAs larger than one kilometer and roughly 15.000 larger than 140 meters.[9] According to NASA no known asteroid poses a significant risk of impact with Earth within the next 100 years. However, due to the incompleteness of the current NEO catalogue, an unpredicted impact such as the Chelyabinsk event could happen at any time.[10]

References:

Center for Near Earth Object Studies (N. J.): NEO Search Program. https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/about/search_program.html (18.04.2021)

Center for Near Earth Object Studies (2021): Fireball and Bolide Data. https://cneos.jpl.nasa.gov/fireballs/ (17.04.2021)

NASA (2019): Did You Know… https://www.nasa.gov/planetarydefense/did-you-know (18.04.2021)

NATIONAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY COUNCIL (2021): Report on Near-Earth object impact threat emergency protocols. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NEO-Impact-Threat-Protocols-Jan2021.pdf (17.04.2021)

Robertson, D. K., Mathias, D. L. (2019): Hydrocode simulations of asteroid airbursts and constraints for Tunguska. In: Icarus Volume 327, 15 July 2019, Pages 36-47.

Van Ginneken, S. Goderis, N. Artemieva, V. Debaille, S. Decrée, R. P. Harvey, K. A. Huwig, L. Hecht, S. Yang, E. D. Kaufmann, B. Soens, M. Humayun, F. Van Maldeghem, M. J. Genge and P. Claeys (2021): A large meteoritic event over Antarctica ca. 430 ka ago inferred from chondritic spherules from the Sør Rondane Mountains. In: Science Advances 31 Mar 2021: Vol. 7, no. 14. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/7/14/eabc1008 (17.04.2021).

[1] NASA (2017)

[2] (Robertson & Mathias 2019)

[3] NATIONAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY COUNCIL (2021, p. 22)

[4] NASA (2019)

[5] NATIONAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY COUNCIL (2021, p. 32)

[6] NASA (2019)

[7] NATIONAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY COUNCIL (2021, p. 32)

[8] Van Ginneken, Goderis, Artemieva, Debaille, Decrée, Harvey, Huwig, Hecht, Yang, Kaufmann, Soens, Humayun, Van Maldeghem, Genge and Claeys (2021)

[9] Center for Near Earth Object Studies (O. J.):

[10] NASA (2019)