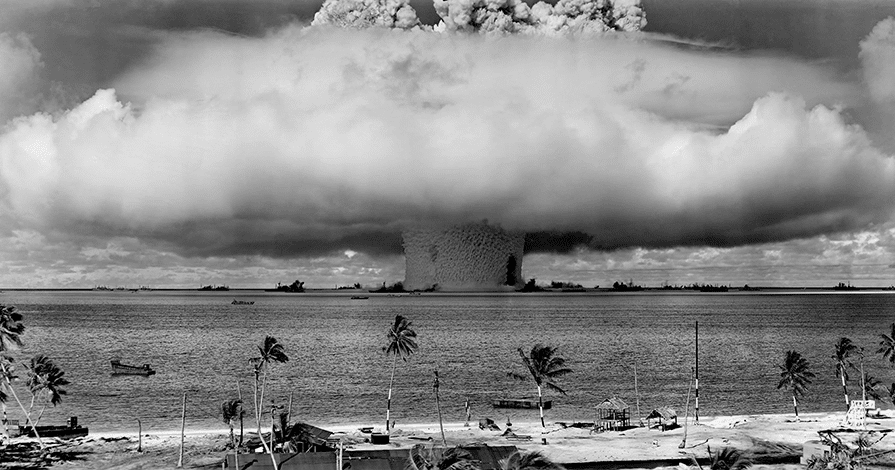

In the morning hours of July 16, 1945, in the remote desert two hundred miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, the first ever nuclear weapon was detonated as part of the US nuclear research program, code named The Manhattan-Project. This event marked the dawn of a new geological age, born out of atomic tests, nuclear detonations, and reactor accidents such as The Chernobyl Incident. Large quantities of radioactive waste were disseminated in the atmosphere, land, and ocean in the form of radioactive isotopes such as Cesium 137, Strontium 90, and most infamously, Plutonium 239, which derives its name from Pluto, the Greek god of the underworld, giving the proposed era its name: Plutocene.[1]

The age of men

Geologists commonly refer to our current time as the Anthropocene; the new age of men in which humans became a geophysical force, capable of affecting the environment on a global scale. This era began roughly around the 1800s, with the wake of the industrial revolution, which led to an unprecedented scale of artificial combustion of fossil fuels, such as coal, gas and petroleum. This resulted in a drastic increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide from a pre-industrial value of 270-275 parts per million (ppm) to 310 ppm by 1950, and to 415 ppm in 2019.[2] As a consequence, the climate shifts to a greenhouse-effect dominated by hot climate, which can be interpreted as the boundary of the late Anthropocene, and the dawn of the Plutocene, demarcated by a layer of Plutonium which continues to emit radiation for the next 24,100 years. In the Plutocene, the temperatures are considerably higher, comparable or above of previous warm periods during the Miocene – Pliocene era between 23 Mio. to 2,6 Mio. years ago, when the global temperatures where on average 2 to 4 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial era.

A mass extinction in progress

A temperature increase of 4 degrees Celsius would cause a humanitarian catastrophe of unprecedented proportions, leading to an increasing rate of human conflict, a rise in sea level of up to 10 meters (32 ft), displacing hundreds of millions from coastal regions, more frequent and prolonged droughts and heatwaves that render large parts of the world inhabitable, as well as the eventual extinction of half the planet’s species.[3] The geological record shows a direct correspondence between temperature trends and greenhouse gas concentration caused by planetological, volcanic, or extra-terrestrial (asteroid) factors and the mass extinction of species.[4] A mass extinction event is a planet wide rapid decrease in biodiversity. As of today, 5 such extinction events are known in geological history.[5] Our planet, however, is currently facing a 6th extinction crisis, with an estimated extinction rate that is 1,000 to 10,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate without human interference. In contrary to prior extinction events, this one is almost entirely caused by humans.[6] Thus the species of Homo sapiens is in the process of destroying the entire biosphere, leading to its own demise.[7]

References:

Glikson, A. (2017): The Plutocene: Portents for the PostAnthropocene Geological era, in: Australian Quaterly, April-June 2017, S. 38-44.

IPCC (2018): Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, S. 32 ff.

Nasa (2019): https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/graphs_v4/

Rötzer, F. (2019): Telepolis: CO2-Emissionen in der Atmosphäre steigen weiter exponentiell.

Wikipedia (2019): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extinction_event

WWF (2019): https://wwf.panda.org/our_work/biodiversity/biodiversity/

[1] Glikson (2017)

[2] Rötzer (2019)

[3] IPCC (2018)

[4] Glikson (2017)

[5] Wikipedia (2019)

[6] WWF (2019)

[7] Glikson (2017)